Before it became a theatre and a major cultural centre in Lisbon, this building was the site of the'emblem of Portuguese justice and power. This building has been the scene of many historic events, and is an important place for Portuguese culture, which continues to evolve while showcasing modern and classical Portuguese culture.

This building was constructed around 1450 to accommodate foreign dignitaries and nobles passing through Lisbon. Due to a lack of space at Saint George's Castle, the king's guests were accommodated in this new building and sometimes in the homes of local residents. At that time, and even just a little earlier, the Inquisition had already taken up residence here. This palace, which bears no resemblance to today's building, was named the Palacio dos Estaus. In the 16th century, the Estaus Palace became the official headquarters of the Portuguese Inquisition under the reign of King John II. The palace took on a special and important function, as both a home for the nobility and a place of religious justice. Located on the Place de Rossio, the palace served as a prison and a religious court, and the people could also attend the execution of sentences handed down in the palace. History remembers above all the example of the writer, philosopher and humanist Damião de Góis, who fell victim to the Inquisition, as did the thirty-three-year-old playwright Antonio José de Silva, who disappeared in the flames.

Ironically, in 1755, the palace was damaged by a terrible earthquake and then completely destroyed by fire in 1836.

After the end of the Inquisition at the beginning of the 19th century, and with the arrival of the Romantic cultural movement, it was decided to rebuild the palace in the neo-classical style, a place reserved for theatrical art. Thanks to the efforts of the poet, writer and politician Almeida Garett, the venue was rebuilt as the D. Maria II Theatre in honour of Queen Maria II (1819-1853).

The Queen's husband was a German advocate of Romanticism. An artist and lover of the arts, he realised that something was missing in Lisbon, and in his search he joined forces with a Portuguese writer, Almeida Garrett, and the two of them began to build a project around the art of theatre in Lisbon. Thus was built the National Theatre and the creation of the actors' school (the conservatory) and the institution.

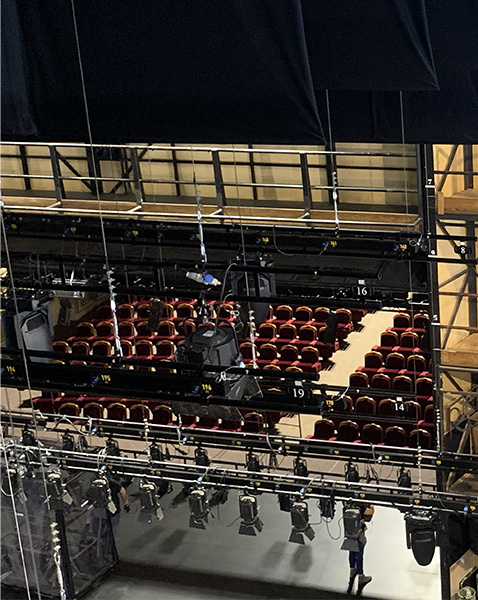

From the outset, the theatre's ambition was to be a national theatre, with troupes of professional actors. The company that had the privilege of performing in the theatre was chosen by competition. A number of troupes stayed for several years, and the venue retains the memory of the talented actors who came and went.

At that time, plays written in Portuguese were performed in Lisbon, but not at the Dona Maria II Theatre. These plays in Portuguese were mostly very fanciful and of poor quality. So, in 1800, at the Dona Maria II Theatre, many people were performing in many languages, apart from Portuguese. They also performed plays in French, Italian and Spanish, as Portuguese was not considered a valuable language at the time.

Then, in the mid-1800s, a feeling of nationalism about the country emerged, as was happening in France and Germany. In Portugal, the nobles in power wanted to revive the past and give people a sense of belonging to this nation. They wanted to use this institution to re-educate people.

The companies that followed were quite free, they paid rent and could play what they wanted, up to a certain point. When the theatre opened, the press was completely free. The king was openly criticised and this was very common: for example, influential people worked in the morning as councillors, in the afternoon as members of parliament and in the evening as journalists. It was a very political operation, and it was also common for the king to write under his own name in the newspapers. It was therefore a completely free press, which meant that everything that was said in the theatre was completely accessible, and this obviously changed with the arrival of the dictatorship.

The theatre's influence on the city

The theatre was a must: people went there especially to be seen, and the show was on stage as well as in the balconies. This practice changed in the 1900s. Until then, it was like opera: spectators were invited by the King. Then, after the French Revolution, everything changed: for the first time, anyone could buy a ticket. The only constraint was that the common people and the nobility could not sit together; social status was very important in the choice of seats. The seats belonged to the group to which they belonged, and everyone went to the theatre. The theatre at that time was a perfect reflection of the structure and organisation of European society. The influence was above all political.

During the dictatorship, the venue remained a theatre, but the organisation within the theatre was different. It was during this period that a company stayed the longest, remaining unchanged for 60 years. Under the Ditadura Nacional, the omertà was de rigueur: there was no criticism of society within the theatre, and even less of those in power. Plays were controlled, texts were checked and censored by the state police.

As Lisbon's culture has changed, so has its theatre. As social events have unfolded, the theatre has witnessed many historical events. Today, the theatre reflects our society, acting as a guardian of classical theatrical culture and welcoming directors who revisit the classics. Totally contemporary plays are also performed, and the theatre has created a second, more intimate auditorium, with no set, to give contemporary creators carte blanche. As when it was founded, the theatre depends on the government budget allocated to culture, giving it complete autonomy and not being subject to the audience for its creations. That's why ticket prices are so affordable, and why making culture and language accessible is such a noble act. The creative process is very avant-garde, and the plays created at the theatre are performed in other venues in Portugal and around the world. The theatre has also opened its doors to visitors, with a guided tour every Monday by Carla Mira who helped me write this article about Lisbon's most emblematic landmark.